Storm Goretti and Beyond: Understanding the Health Toll of Extreme Weather

- Posted on: 26 January 2026

The recent weeks have brought stark reminders of the UK’s vulnerability to extreme weather. Storm Goretti left thousands of homes without power and water, schools closed for days and basic services were interrupted across the UK with some residents still confronting damage weeks later.

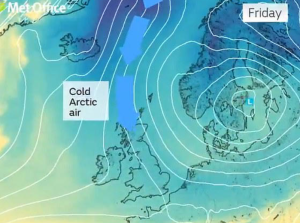

Meanwhile, over the New Year period the UK Health Security Agency issued an amber cold health alert as temperatures plummeted, warning of serious risks to vulnerable populations.

Right now as this blog goes out and overnight, Storm Chandra is pushing across the UK with more than 100 areas on flood alert and yellow warnings of snow for Scotland.

![]()

![]()

These aren’t isolated incidents – they’re part of a pattern we need to understand and prepare for.

What connects power cuts, cold snaps, and ice, snow and flooding isn’t just their disruption to daily life, but their profound impacts on health. When the lights go off, medical equipment stops working. When temperatures drop, excess deaths rise. When infrastructure fails, the most vulnerable among us – older people, those with chronic conditions, people living in fuel poverty – bear the greatest burden.

The UK climate is changing rapidly as noted in the Fourth UK Climate Change Risk Assessment and significant impacts are now caused by extremes of heat and rainfall, as well as from rising sea levels. Extreme weather events may become more frequent and intense for some, creating compounding health risks that our systems need support to adapt to.

We asked experts from across the Net Positive Centre to come together to help us understand what recent events reveal about the climate-health connection – and what we need to do differently.

What are the immediate health risks when extreme weather events coincide or happen in quick succession?

When extreme rainfall, floods, storms and cold snaps hit in quick succession, the risks multiply rather than simply add up. Power outages during freezing temperatures mean people can’t heat their homes safely, while also threatening home oxygen concentrators, refrigerated medications, and vital communication channels. We also see healthcare systems struggling to respond when roads are impassable and staff can’t reach facilities, just as demand for emergency services peaks with cold-related illness and weather injuries.

What are the mental health and wider social impacts of extreme weather events?

Extreme weather events don’t only cause physical health impacts but can have both immediate and long-lasting effects on the mental health of individuals and the ability of households and communities to cope with the effects of extreme weather. The effects of flooding events, for example, can be highly traumatic because of the disruption this causes to people’s homes, often impacting on family life and putting strain on personal relationships and household finances. People can also experience flash-backs and high levels of anxiety triggered by heavy rain, for example. Indeed, the geographical distribution of the impacts of extreme weather can exacerbate underlying social inequalities (for example, in areas with higher levels of deprivation) and further increase vulnerability in communities.

Who are the most vulnerable during extreme weather events like these?

Older people and those with chronic conditions like respiratory or heart disease face the highest immediate risks, as cold temperatures and stress can trigger serious health events. People living in fuel poverty often can’t afford adequate heating even when power is available, while those in poorly insulated housing lose heat dangerously fast during outages. Indeed, people living on low incomes are often the least able to cope with traumatic events like flooding, as they may not be able to afford insurance and the immediate costs of coping with extreme weather disruption. We also need to consider people who depend on powered medical equipment, those with limited mobility who can’t easily evacuate or seek help, and communities in isolated areas where infrastructure takes longest to restore.

What are the actual health implications when people lose electricity for days, particularly during cold weather?

Beyond the obvious heating loss, power outages can cut off medical devices that people depend on such as nebulizers, powered wheelchairs, electric beds and refrigerated medications like insulin. Hypothermia risk rises sharply, particularly for elderly people who may not recognise their own symptoms. Food spoilage and lack of clean water create additional risks, while the inability to charge phones, use emergency personal alarms or call for help leaves vulnerable people isolated during a health emergency.

How vulnerable are the systems our health infrastructure depends on – water supply, power grids, transportation networks – to climate extremes?

Our critical infrastructure was designed for yesterday’s climate, not tomorrow’s extremes, creating dependencies we’re only beginning to understand. When water is cut off it doesn’t just affect homes – it can threaten infection control in care facilities and hospitals. The interconnected nature of these systems means failures cascade: no power means no water pumping, no water means healthcare facilities are challenged, blocked roads mean no fuel deliveries to restart generators.

Are there long-term health consequences beyond the immediate crisis period?

The health toll extends far beyond the storm or flood itself. People who lose heating for days may develop respiratory infections that persist for weeks, while the stress and anxiety of experiencing severe weather events can trigger lasting mental health impacts. Disrupted medication regimes during power outages can destabilise chronic conditions like diabetes or heart disease. For communities repeatedly hit by extreme weather, there’s also a cumulative psychological toll – the constant worry about “when will it happen again” that we’re seeing in areas that faced both flooding and severe cold this winter.

What can we learn from these events in terms of protecting health during extreme weather?

These events show us that early warning systems and community networks are vital. We need to move beyond individual resilience to community-level preparedness, backup facilities are ready before events hit, not scrambled together during crisis. The most effective responses combine infrastructure investment with social systems: resilient power grids matter, but so do organised check-in systems for isolated residents and pre-positioned medical supplies in at-risk areas.

What are the implications when events hit headlines then shrink from view?

The danger is that we treat each extreme weather event as a one-off emergency rather than recognising the pattern and preparing for the next one. Recovery isn’t just about restoring power – it’s about identifying who struggled most and why, strengthening vulnerable systems, and learning what worked. When attention moves on quickly, we miss the opportunity to capture these lessons while they’re fresh, and vulnerable populations who are still dealing with health consequences or property damage can feel abandoned. The rhythm of crisis and forgetting prevents us from building the sustained, systematic resilience we actually need.

Is it possible to find a constructive approach to these events and what might this look like?

Crises like Storm Goretti can reveal exactly where our systems are failing and who’s falling through the gaps – information that’s invaluable for building genuine resilience. A constructive approach means capturing those lessons quickly while coordinating research, public health responses, and community feedback to understand what worked and what didn’t. It also means recognising that communities aren’t passive victims – during Storm Goretti, we saw neighbours sharing generators, community centres opening as warm spaces, and local groups organising welfare checks. By using evidence of what works well, we can adapt our services, systems and communities and this can have wider positive benefits in terms of building healthier, happier and more resilient ways of living into the future, ensuring that adaptation is not a wasted investment and that serves us well beyond the next storm.